The Russian government has attempted to centralize control of the internet in recent years. Its efforts take many forms, including creating a domestic intranet to ensure that all Russian traffic passes through the regulator’s servers, and enhancing the state’s ability to swiftly take down any content that violates local restrictions.

However, while these stories might dominate the headlines, they offer only a small glimpse of the overall digital landscape in Russia. For a clearer view, it’s important to consider Russia’s internet holistically. To this end, we’ve created a country profile containing all kinds of information about the country’s digital awareness, privacy laws, and network availability.

Internet penetration and availability

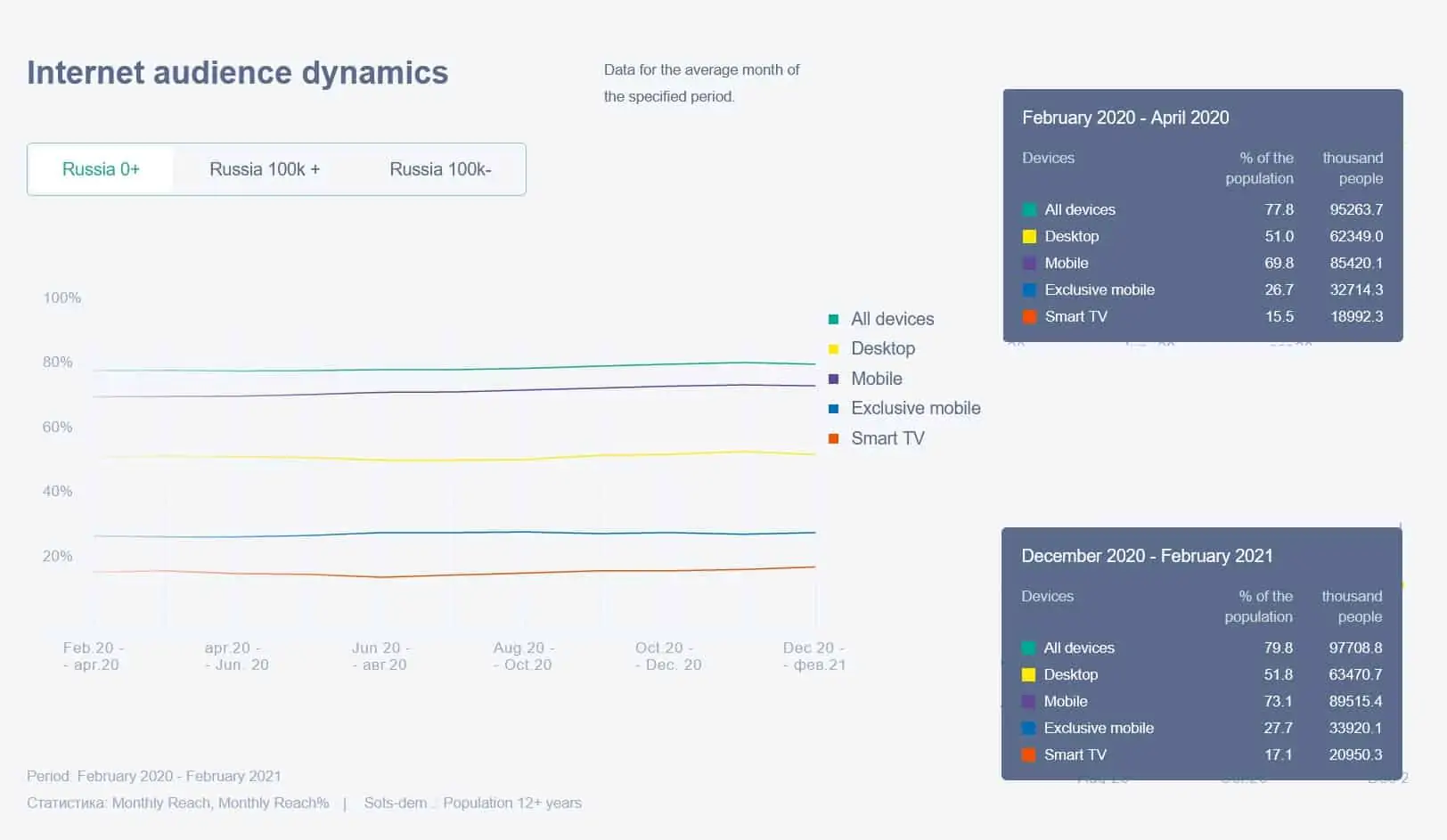

While it’s unclear exactly how many of Russia’s citizens are internet users, research from the CIA, World Bank Group, and Mediascope agrees that the country has internet penetration of about 80%. Where older data is available, it tends to show slow but sustained growth in this area. Mediascope identifies mobile users as the fastest growing demographic, with 73.1% of internet users browsing on a phone or tablet in Q1 of 2021, up from 69.9% at the beginning of 2020.

Although metropolitan areas tend to have faster, more reliable internet connections than rural ones, almost everyone has the ability to get connected. This is largely due to Russia having among the most-affordable internet plans in the world. Cable.co.uk found that on average, Russians paid just $7.50 USD per month for broadband, with an annual increase of about $0.15. The only countries that are less expensive are Ukraine and Syria, at $6.41 and $6.69 per month, respectively. For context, the average American pays $59.99 per month.

Public wifi hotspots are widely available too. Wifimap.io claims that there are over 250,000 free networks across the country, with Moscow offering the most (36,708). These cannot be used anonymously, since users must verify their identities by providing a phone number, a code (sent via SMS), or some form of photo ID (such as a passport).

Internet speeds in Russia

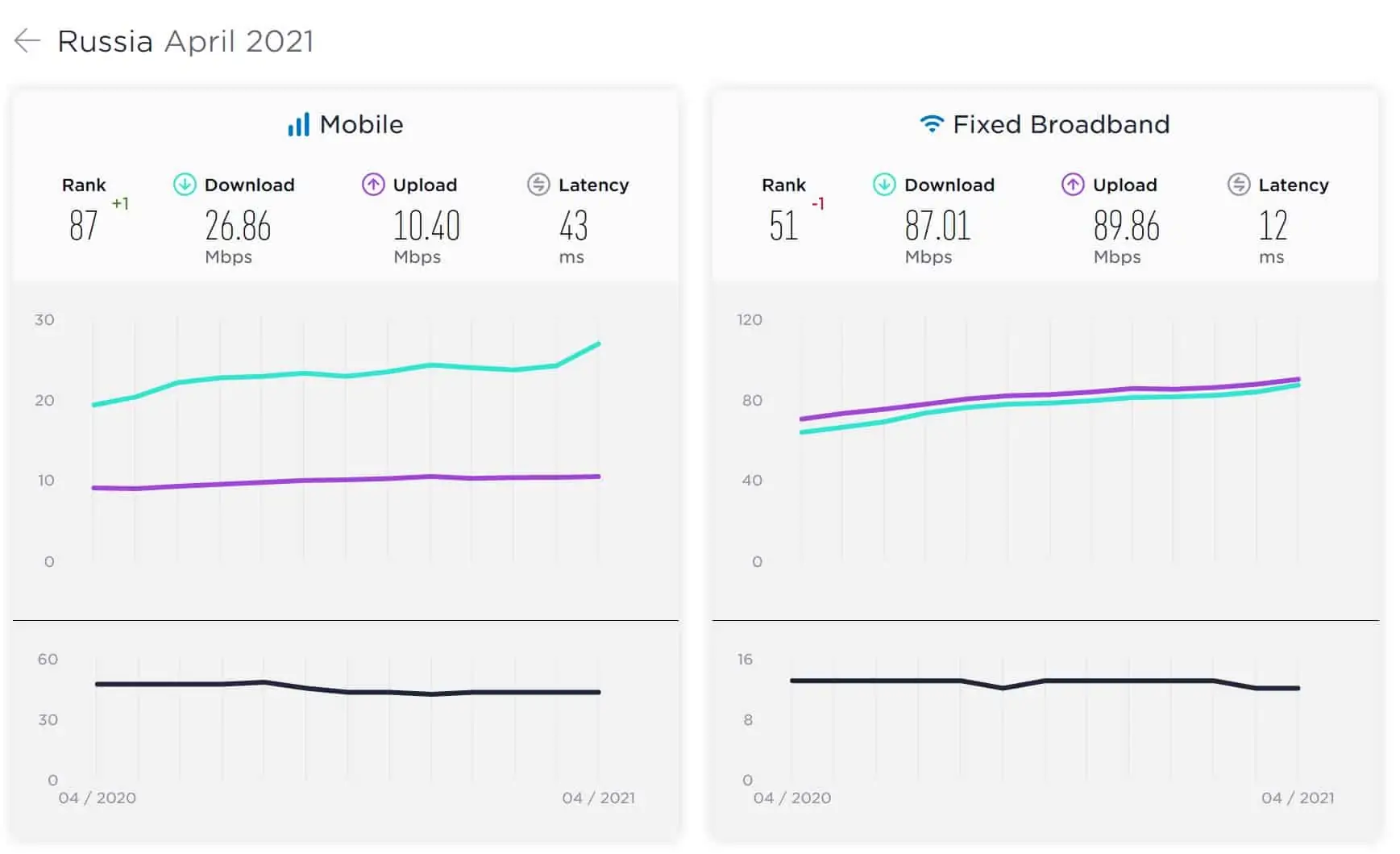

The Speedtest Global Index by Ookla indicates that as of April 2021, the average mobile internet speed in Russia was 26.86 Mbps, while the average fixed broadband speed was 87.01 Mbps. This is slower than what users in the US can expect (191.97 Mbps on average) but is broadly in line with the average British (92.63 Mbps), Australian (77.88 Mbps), or Italian (90.93 Mbps) connection.

Interestingly, Russians have a significantly higher average upload speed than any of these locations, at 89.96 Mbps. In other words, in Russia, upload speeds are usually about the same as download speeds. It’s unclear as to why this is, but it may be due to optimization done during the country’s work on creating its own separate version of the internet.

Digital awareness

There is a lack of English-language research on the general cyber-awareness of Russian citizens. However, after analyzing 75 countries using 15 cybersecurity-based criteria, the UN’s 2018 Global Cybersecurity Index found that Russia was the 12th worst for cybersecurity.

This index revealed that 18.21% of Russian computers flagged a potentially malicious program during the reporting period. In the same period, 3.55% of desktop PCs and 1.49% of mobile devices were actively infected. Additionally, Russians are the target of 6.29% of all malicious emails; the only countries targeted more frequently are Spain and Germany.

Online anonymity

The Russian government has several laws designed to reliably identify internet users. For instance, 374-FZ and 375-FZ (known collectively as the “Yarovaya law”) require websites and services to assist the FSB in cracking any encryption they might use, under penalty of a steep fine. Additionally, the law says that apps have to store all of their users’ communications for at least six months. Metadata (including the time a message was sent, and where it was sent from) is stored for even longer: a full three years.

Given that customers are asked to show ID when purchasing a SIM card or connecting to a public wifi hotspot, it is extremely difficult to connect to the internet anonymously in Russia. Further, users must provide a valid phone number when signing up for social media sites. This allows authorities to say with a reasonable level of certainty who a particular user is.

Access to privacy tools

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are still legal in Russia, provided you don’t use them to access content that’s blocked by the government. However, the passage of Federal Law No. 276-FZ, the so-called “VPN ban”, requires VPN providers to share their users’ information with the government and to prevent people from circumventing the country’s online restrictions. Providers that fail to do so risk having their websites and services made inaccessible.

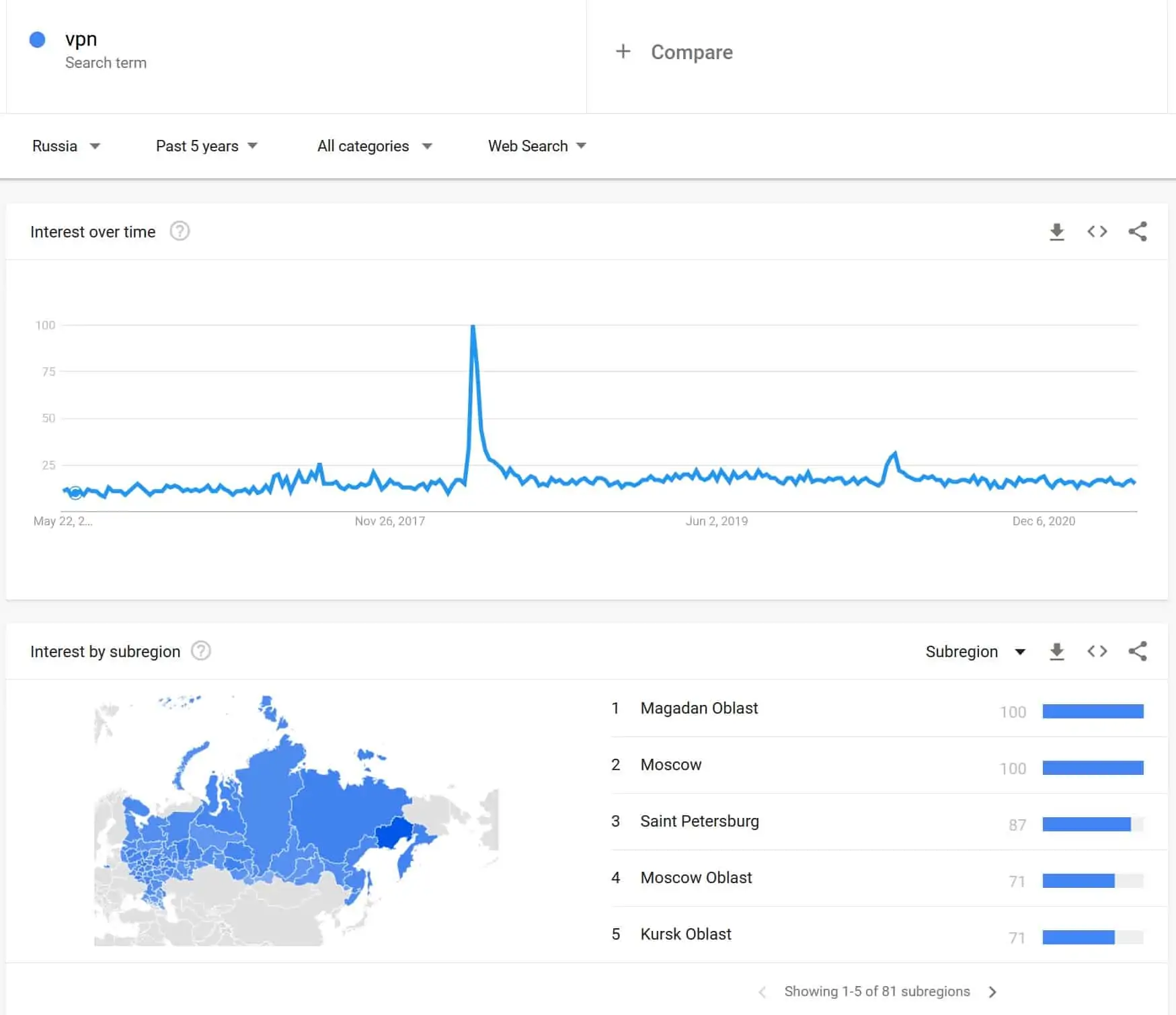

A 2018 report on media consumption found that 22% of Russians aged 18–24 used Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), with an adoption of around 10% in other age groups. GlobalWebIndex’s VPN Usage Around the World survey from the same year found that 42% listed anonymity, unblocking content, or staying in touch with family as a main reason for using this technology.

Despite this, it’s still unclear how many Russians use VPNs today. This is because there was a huge spike in interest around April 2018, when access to the encrypted messaging app Telegram was blocked by the government (this blocking proved ineffective and was later reversed). Further, the coronavirus pandemic saw VPN usage rise globally, meaning it’s likely there are far more VPN users in Russia now than existing research would suggest. The most reliable information available at this point is AtlasVPN’s VPN Adoption Index, which claims that around 5,000,000 Russians (or 3.37% of the population) used a VPN in 2020.

New and complex privacy tools clearly don’t intimidate Russian users. In fact, the only country with more Tor users is the United States. These two countries account for 17.88% and 18.48% of all Tor users, respectively. Likewise, a 2020 survey by Deloitte found that 50% of Russians asked had Telegram installed on their phone, up 10% year on year.

Cybercrime: prevalence and attack types

In 2017, Securelist found that of the 60+ new crypto ransomware variants, 47 (or over 75%) came from Russian-speaking groups or individuals. It speculates that skilled Russian programmers were simply waiting for a new monetization avenue to appear so that they could recreate a spate of ransomware attacks that hit Russia in 2009 on a global scale.

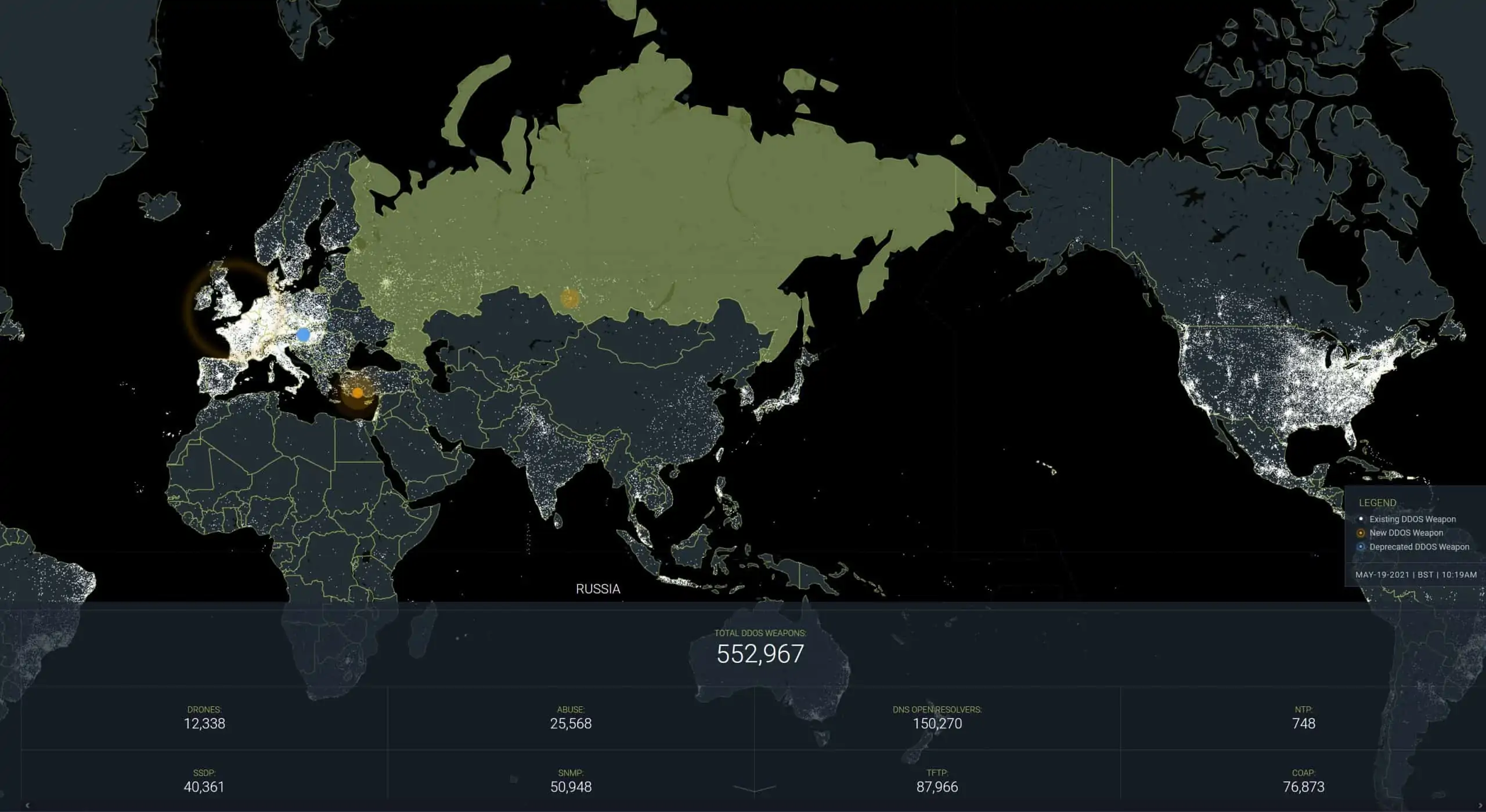

There’s a significant amount of automated activity coming from Russia too. Spamhaus ranks it as the third-worst country for spam, following China and the US. Russia does have an undersized amount of bot activity, though, ranking tenth globally with around known 161,200 botnets. Meanwhile, A10’s threat intelligence map suggests that there are roughly 553,300 DDoS weapons in Russia. This is quite a high number, but is still substantially lower than in the US (3,584,000 weapons) and China (2,997,000 weapons).

The question remains: why are so many hackers from Russia? There’s no definitive answer to this, but one suggestion is that the country’s education system places greater emphasis on teaching programming fundamentals and concepts during early years. In fact, Russian children may even begin learning the basics of information technology at as young as six years old. US students, on the other hand, won’t begin learning about these more in-depth topics until high school at the earliest.

When you consider how well these hacks can pay compared to a traditional job, it’s not difficult to see why hacking can seem like an easy route to a higher standard of living. After all, a single gang stole almost two billion roubles in 2017. For context, the average monthly salary is 51,000 roubles.

Blocked content

Russia’s Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (known as Roskomnadzor) maintains a list of websites blocked in Russia. Unfortunately, however, this isn’t publicly available. Instead, internet users have to manually check whether a website is blocked in Russia using a government portal.

Ostensibly, Russia blocks websites for hosting the following content:

- Pro-drug content

- Illegal pornography

- Gambling sites that violate local laws

- Pro-extremist material

- Information regarding suicide

However, while these sound like fairly specific restrictions, they’re broad enough to make the case against almost any social media platform. Often, this leads to partial censorship, with specific channels, content providers, or pages blocked. In fact, to date, Russia has submitted the 2nd most takedown requests to tech giants. In March 2021, the government even attempted to restrict users’ speeds on Twitter, following the platform’s refusal to take down a few thousand controversial posts.

The government frequently makes the case against encrypted services too, claiming that they provide cover for terrorists. Critics argue that these services are necessary, citing the country’s creeping censorship and laws that already “intimidate journalists into silence”.

Privacy and data protection

Russia scores very poorly in terms of overall privacy. In fact, our research found that it has the second-worst data protection policies in the world, after China. There are multiple reasons for this, and we’ll list a few of the most serious below:

- The government can request any data it likes, from any company, and threatens those that don’t comply with blocking

- Biometric data collection is widespread and unavoidable. For instance, you cannot obtain a visa without providing your fingerprint. As a result, the country’s biometrics data (which police can access freely) contains most of the nation.

- Legislative protections are routinely overruled. For instance, Russian law allows it to rule any judgement from the European Court of Human Rights unconstitutional and thereby, unenforceable

- Effectively no oversight on surveillance. Technically, authorities require a court order to access communications data. However, in 2019, courts granted 99.8% of all requests.

- Websites must keep all communications data for a minimum of six months

- Anonymous web browsing is near-impossible

- Security services monitor social media and perform sentiment analysis to keep track of the country’s overall political temperature

- CCTV cameras using facial recognition technology are extremely common. Moscow is the world’s 13th most-surveilled city, with 193,000 CCTV cameras — 199 for every square mile.

- The country has successfully trialled its own walled-off version of the internet, similar to the one China has. This would make it even easier to restrict content and monitor internet users.